Climbing Jacob's Ladder

Monastic residency program provides the ladder to escape the pit of addiction

The three-mile, 28-curve climb on US Route 50 from Erwin to Aurora is arduous in good weather, deadly in snow and ice. The bucolic Aurora scenery is worth the exhausting climb. Foremost is the awe-inspiring Cathedral Woods, a hemlock climax forest protected as a state park. The mature forest coddles Brookside Farm, a piece of misplaced New England agriculture with its assortment of red barns and sheds, stone house and verdant hillside pastures.

More than a century ago, city folks came from sweltering East Coast cities on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to be fanned by the breezes that blow across porched cottages set along the hill across from the forest and farm. Thrice daily, protein and vegetables from the farm were served to vacationers. And from first light to gloaming, the hemlock sanctuary invited awestruck travelers to ascend its ladders of majestic consciousness.

While the tourists are long gone, several of the cottages, the forest, and most of the farm remain. Collectively, they provide the setting and residences for Jacob’s Ladder. On any given day, a dozen labor on this mountain as they ascend 12-runged ladders lowered into the pit of substance abuse. As with the highway ascent to this place, the climb is steep, arduous and treacherous. The very lives and futures of these men dangle from the rungs, which are customized to reach lives of sustained recovery and freedom from chemical demons.

“It’s a residential treatment that shows you, more than anything else, how to work for yourself,” said Aidan, an 18-year-old from Mississippi and Jacob’s Ladder graduate. “That’s the biggest thing I’ve gained out of here. I think the backbone behind everything is teaching us that if we want it, we have to go out and get it for ourselves. It’s a great program and it’s changed the course of my life.”

This melding of working farm, natural area, repurposed resort and treatment program was the first of its kind for West Virginia when it opened on March 15, 2015. Licensed by the West Virginia State Board of Behavioral Health, Jacob’s Ladder accepts private pay and government and private insurances. Participants live a monastic lifestyle for six months, with no access to social media and only 30-minutes of family contact time per week.

Neither the Jacob nor the ladder has spiritual moorings; rather, the ladder represents the Twelve Steps of Narcotics Anonymous, one of several approaches used at the residential treatment center. The Jacob comes from the program’s inspiration, Jacob Blankenship. Chad Bishop, director of operations for Jacob’s Ladder, told me that the program was born of personal experience—the founder, Dr. Kevin Blankenship, needed drug addiction treatment for the family member but could not find long-term residential care within West Virginia. Drawing upon his many experiences and relationships as an emergency medicine professional, he assembled a team that nurtured Jacob’s Ladder from a concept to a working program.

“When this first started, we spent a whole month just learning about each other, who we were and how we could make things work,” Chad said. “Doctor Blankenship’s idea was we were flying a plane with no wings, and we were building it as we went along.”

From ‘bankruptcy’ to thriving

Jacob’s Ladder is for men ages 18 and older. They live in a dormitory and share the housekeeping chores. An open-enrollment approach means that both newcomers and veterans nearing the end of their six-month treatment are living, healing and growing together.

“I was bankrupt when I got here,” said E.P., a 40-year-old participant from Vermont. “You know, I have overdosed I don’t know how many times, but coming here made me feel more welcome, to the hills and stuff. … It’s saving my life.”

Six months is much longer than most programs, but the protracted term contributes to the program’s success. J.T., at his graduation ceremony, said an intake counselor reminded him that “Your life is worth at least six months of time” when he first questioned the extended commitment.

“And that’s one of the greatest things I learned up here, that our lives now together are worth so much,” said J.T., a Virginia resident. “And it took me some time to remember that. It took me some hard times to remember that.”

“You guys reminded me how much life I have and how much life there is, even in people that sometimes get given up on,” J.T. told his family, staff and other program participants at his graduation.

“We all live together, we all have each other’s backs,” Aidan said. “My first impression was that the guys here were really welcoming. I knew I was in the right place.”

“This is the most loving rehab I have ever been through,” said S.S., a 36-year-old Indiana resident who had five previous treatment experiences. “The people who work here really care and want to make you successful.”

A multi-disciplinary approach that “treats the whole person, not just addiction” imbues the program. Upon intake, each participant undergoes chemical, psychological, nutritional and medical assessments. The program’s professionals then develop a personalized treatment plan. Collaborations and meetings between the addiction counselors, chemical dependency technicians, farm manager and arts/music director provide ongoing assessment and tweaking of the treatment.

Participants frequently cite the experiential, guided mindfulness training as empowering resources that help them navigate situations that would otherwise lead to a relapse. The website for Jacob’s Ladder notes that, “in isolation, addicts find themselves quarantined to their own diseased thinking and therefore anxious, despairing, and addicted. Through mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, addicts are promised ‘a reprieve from self’ (or self-obsessive thought) based on the maintenance of spiritual living.”

“It’s all about having a steady routine each day,” Aidan said. “What am I going to do when I wake up? What am I going to do when I go to sleep? Maintaining a healthy routine is a big thing for me. That’s definitely what is going to be keeping me on track when I leave.”

“We are all just treading water,” said Brandhi Irvon Gafeney, director of music and art for Jacob’s Ladder. “And you inherit treading water rather than learning to really swim and be comfortable. We learn to pursue happiness rather than joy. And that joy is a mindfulness place. It’s a mindfulness state. Like, ‘let me get a good car; that would make me happy.’ But what about the joy that is in getting that car? I think that is what eludes us.”

Brandhi guides the participants into this process of self- and joy-discovery by giving them mindfulness tools in weekly, individualized sessions. At their first meeting, he gives a journal to the client for documenting his emotions and thoughts. These written phrases become the lyrics for a personalized music video that Brandhi produces. Filled with poignant and expressive statements about pain, loss and newfound hope, the music video becomes the individual’s personal mantra of recovery that moves him toward a previously unknown love and respect for self.

“You send somebody out with a song and a video of what they can be,” Brandhi said of the projects.

“I think the best tool I’ve come out of here with is just learning to love myself,” said S.S., addicted for 15 years. “That’s something that I really struggled with beforehand. I had really low self-esteem. And that’s been something that has really blossomed in my time here. I really started to appreciate who I am and understand who I am and start to love myself, because I didn’t understand who I was before.”

Jacob’s Ladder provides residents with a variety of musical instruments, as well as the recording equipment and studio for capturing and honing their musical expressions. For those who express themselves through visual arts, a studio provides painting and stained-glass making supplies.

The landscape inspires creativity and reflection, with Cathedral State Park within walking distance and rolling farmland throughout the Allegheny Plateau community.

Continued next week

Please support this work!

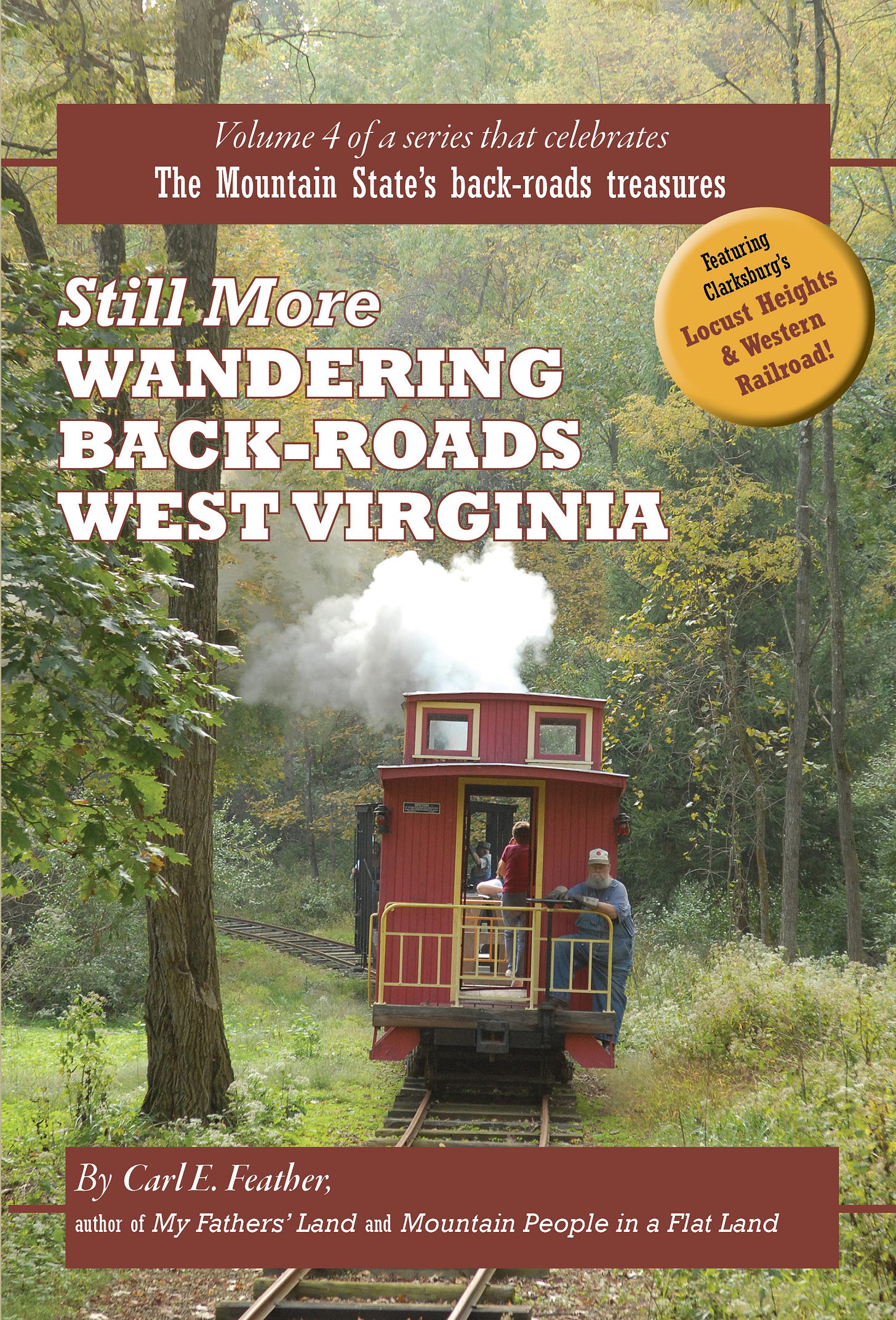

With Goldenseal magazine no longer being a print magazine and lowering its honorarium payment rate to an unsustainable level, I rely upon royalties from my Wandering Back-Roads W.Va. book series and other titles to fund this free Substack. Please encourage your online friends to subscribe and check out our books at books.by/feather-cottage-media.